- After World War II, there was no doubt that aircraft carriers were the dominant naval weapon.

- By the end of the war, the Allied powers had nearly 200 carriers in service.

- The Axis powers had their own plans to build carriers, but their flattops couldn't turn the tide.

After the Battle of Midway, there was little doubt that the aircraft carrier had become the dominant naval weapon.

At the start of the war, many navies envisioned flattops in a support role for battleships, but by 1945 their roles had reversed, with battleships becoming escorts for carriers.

By the end of the war, the Allies had nearly 200 carriers in service. In the Atlantic, they helped defeat the U-boat menace. In the Pacific, they were vital to the island-hoping campaign and were the deciding factor in some of the most important naval battles in history.

The Axis powers' own aircraft carrier ambitions, meanwhile, are often overlooked. Germany and Italy nearly completed their own flattops that they hoped would even the odds at sea. Japan had success with its flattops early in the war, but even the largest carrier it ever built wasn't able to stave off defeat in the war's final months.

Graf Zeppelin

Aircraft carriers were a centerpiece in Germany's pre-war naval rearmament program. Officially known as Plan Z, it called for a Kriegsmarine centered on a force of four aircraft carriers and 10 battleships, though the plan was later revised to only two carriers.

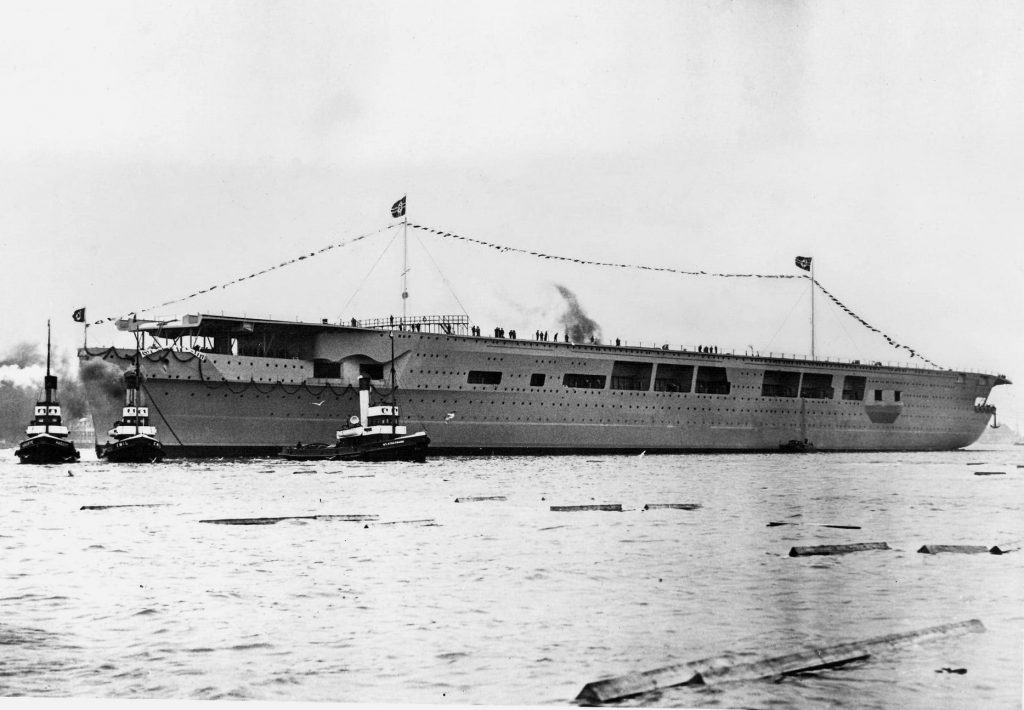

Germany's first carrier was laid down in December 1936 and launched two years later. Named Graf Zeppelin, it was 860 feet long and had an armored deck and hull, giving it a full displacement of over 34,000 tons. The ship's compliment would include 1,700 crewmen and 300 flight crew.

The carrier had a unique system of two 75-foot-long catapults at the forward end that used compressed air to launch aircraft.

The catapults could launch a dozen or so planes in about six minutes before the tanks needed to be refilled, which took almost an hour. This would have allowed Graf Zeppelin to launch and land aircraft at the same time. Aircraft could launch conventionally if the catapults weren't available.

The air wing was to be made up of 20 Fi 167 torpedo bombers, 10 Bf 109s, and 13 Ju-87 Stuka dive-bombers.

Graf Zeppelin was also heavily armed. It had 16 5.9-inch guns in eight casemates for anti-ship defense and 12 4.1-inch guns in six turrets as the primary air defense, supplemented by over 40 smaller-caliber anti-aircraft guns.

Graf Zeppelin was about 80% complete when the war started in 1939, but it never saw service. Germany's needs on the ground and in the air quickly overtook those of the naval front, and its limited industrial capacity was prioritized accordingly.

There was also a rivalry between the Kriegsmarine and the Luftwaffe, whose pilots would be the ones flying from the carrier. While the Kriegsmarine wanted new carrier-based aircraft, the head of the Luftwaffe, Hermann Göring, was focused elsewhere.

Germany's second carrier was laid down in 1938 but cancelled a year later. Work on Graf Zeppelin continued sporadically until 1943, when the Kriegsmarine was ordered to focus on U-boat production instead.

The carrier spent its final two years as little more than a stripped hulk moving between Baltic ports. The Germans scuttled it in Stettin in March 1945. The Soviets raised it in 1946, only to sink it as a target ship in 1947. It was rediscovered by a Polish oil-survey ship in 2006.

Aquila and Sparviero

Italy debated constructing a carrier before the war but ultimately decided against it, choosing to focus on building battleships and cruisers to counter France's naval buildup, which the Italians considered their most immediate threat.

The British attack on Italian ships at Taranto in November 1940 showed the value of naval aviation, and Mussolini ordered the ocean liner Roma be converted into a dedicated fleet carrier in January 1941. Italy's disastrous defeat at Cape Matapan two months later further convinced Mussolini of the carrier's value, and construction began in earnest that November.

Re-commissioned as Aquila, the carrier was 772 feet long and had a full displacement of about 27,000 tons. Its air wing would have consisted of about 36 Reggiane 2001 fighter-bombers launched with the same catapult system as Graf Zeppelin. The carrier itself was armed with eight 135mm dual-purpose guns and 126 20mm anti-aircraft guns.

By September 1943, Aquila was close to 90% complete and was undergoing docking and engine trials. Final completion was set for December, followed by operational capability in summer 1944. But Aquila never made it into service.

Italy's surrender on September 8, 1943 led to the Germans occupying Genoa, where they placed the unfinished carrier under guard and stripped it of anything valuable.

The Allies worried the Germans would finish building Aquila or sink it in an important waterway. They attacked it with an air raid in June 1944 but did limited damage. In April 1945, Italy's Allied-aligned government tried unsuccessfully to sink it with a commando raid. The retreating Germans partially scuttled it in Genoa's harbor later that month.

Aquila's hulk was re-floated in 1946 and moved to La Spezia in 1949, where it was scrapped in 1952.

The Italians were also working on Sparviero, another converted ocean liner, in Genoa in September 1942. It would have been about 760 feet long and displaced about 30,000 tons and carried about 40 aircraft, but it was never completed.

World War II's largest carrier

Germany and Italy struggled to get their carriers operational, but Japan had no such difficulties.

At the start of the war the Imperial Japanese Navy had 10 carriers in service and the most experienced naval aviators. Japan was so good at building flattops that even its army operated its own carriers.

However, as the war progressed it became clear that Japan's industrial base could not replace its losses, especially carriers, which required considerable time and resources to build.

Japan tried to compensate by converting warships and merchant liners into aircraft carriers, which it and other Western navies already had experience doing, but some of the converted carriers arrived too late to make a difference.

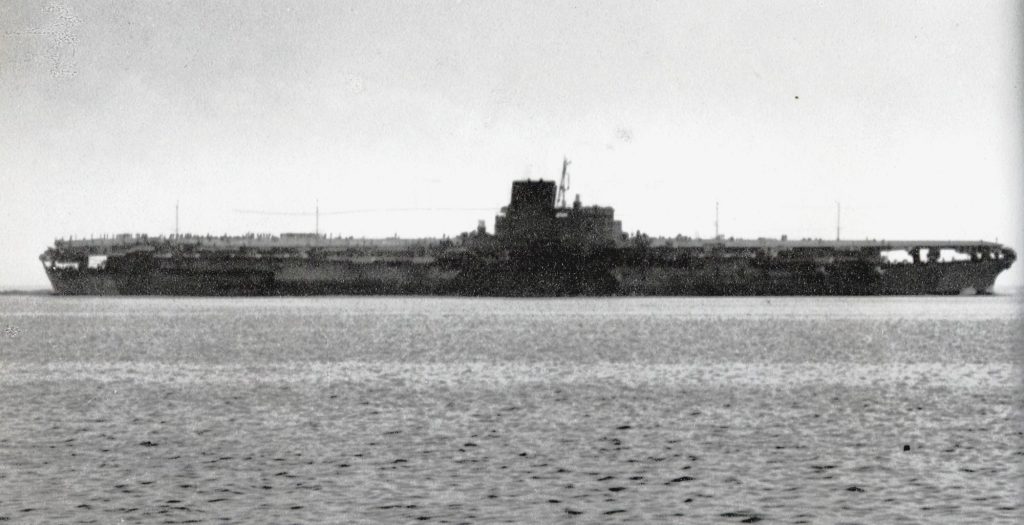

Shinano, for example, began construction in 1940 as the third Yamato-class battleship, the largest and most powerful battleships in history. Work on the battleship Shinano was halted after Midway in 1942, when it was decided to convert it into a carrier to make up for the losses sustained there.

When it was finally launched as a carrier on October 4, 1944, Shinano was 872 feet long and displaced over 70,000 tons.

With a crew of more than 2,000, Shinano was supposed to have its own air wing of 47 aircraft and room for dozens more with which to resupply other Japanese carriers, allowing them to stay at sea for longer. (Given the heavy losses among Japanese pilots by late 1944, that kind of resupply effort was likely unviable.)

Shinano was completed and commissioned on November 19, 1944. On the evening of November 28, it sailed from Yokosuka to Kure to finish being fitting out. After that, it was to transport 50 Yokosuka MXY7 Ohka rocket-powered kamikaze aircraft and other weapons to Okinawa and the Philippines.

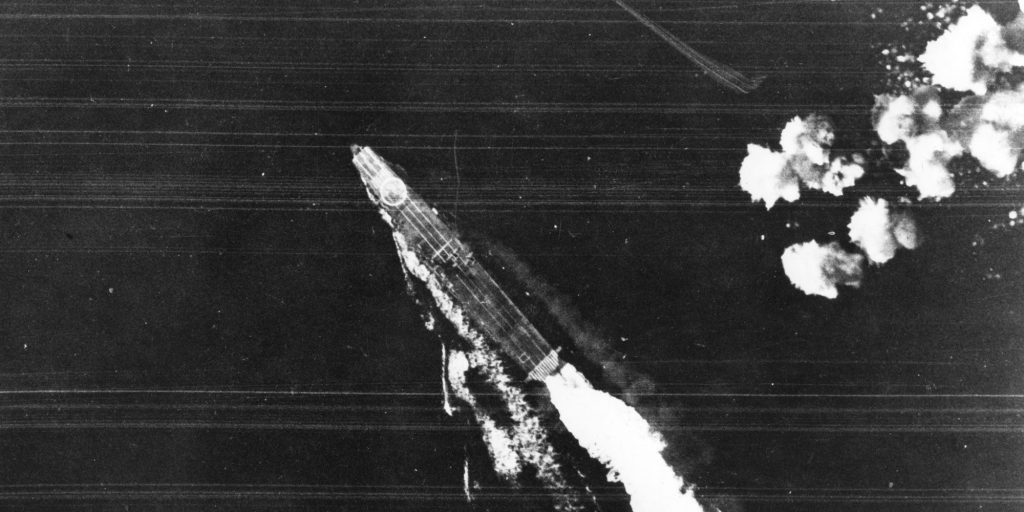

Early in the morning on November 29, however, Shinano was struck by four torpedoes fired from the submarine USS Archerfish. It sank hours later with over 1,400 of its crew. It remains the largest warship ever sunk by a submarine.

Dit artikel is oorspronkelijk verschenen op z24.nl